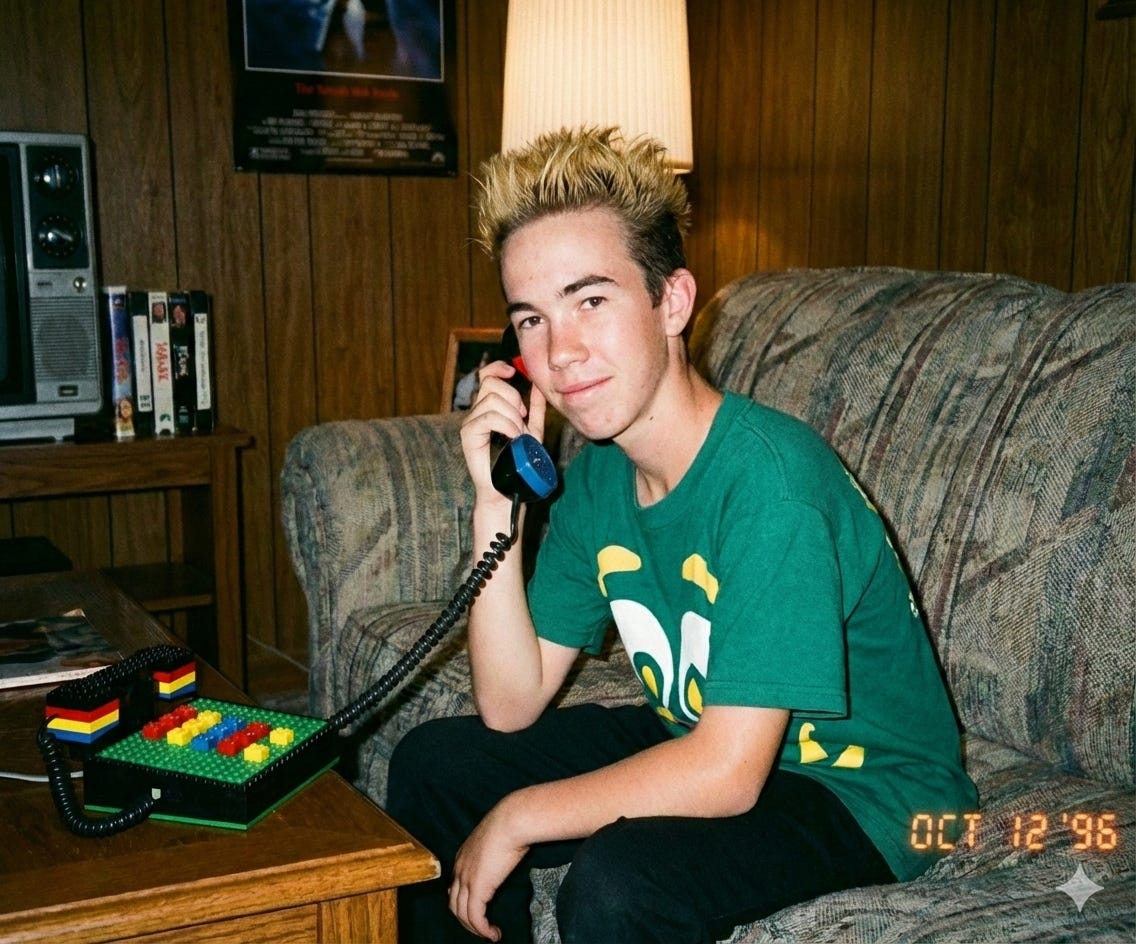

In 1997, I had a private phone line in my bedroom. Not because I was spoiled; because I was relentless.

Every night, I’d make my “rounds.” That’s what I called them. I’d work through my mental list: call Kellie, call Beau, call Amy, call Mandy, call whoever else was in rotation that week. We’d talk about nothing. Everything. The conversation itself was the point.

I recently found my high school journal from that summer. On July 30, 1997, I wrote: “Then I made my rounds and talked to everybody.”

A month later: “She wants to be included in the rounds.”

And this one kills me: “Christine keeps getting grounded from my rounds because she never calls me back. (She can never say goodbye on the phone, she always has to say she will call you back.)”

I had a system. People wanted to be part of it. And I had consequences for people who didn’t reciprocate.

I was sixteen. I didn’t know why I needed this. I just knew that something settled in my nervous system when I could hear someone’s voice, follow the thread in real-time, and feel held in the exchange.

Thank God I grew up before texting existed.

Because here’s the thing: I now have 47 unread text messages. Some are from people I love. Some are from weeks ago. And every time I see that notification badge, I feel a specific kind of shame; the shame of being a “bad friend,” a “bad texter,” someone who should be better at this by now.

For years, I thought this was a character flaw. A discipline problem. Something I could fix with the right app, the right system, the right amount of willpower.

I was wrong.

The Reconstruction Tax

Here’s what nobody tells you about asynchronous communication: every gap between messages creates a context void.

When I return to that text thread from three days ago, I’m not continuing a conversation. I’m reconstructing it from textual artifacts. That means:

Re-reading to figure out where we left off

Trying to recover my emotional state at the time

Modeling where they are now (which may have shifted)

Rebuilding the relational context (are we good? was my last message weird?)

Then finally formulating a response

That’s an enormous cognitive tax paid before I can even engage.

For most people, this happens automatically. Their working memory holds the thread. They can pick up where they left off without the full archaeological dig.

My brain doesn’t work that way.

Synchronous Communication as External Scaffolding

Here’s the insight that finally made it click: in live conversation, the other person becomes my working memory scaffolding.

They’re holding the thread. They’re providing real-time feedback loops. Their tone, pacing, and responses create a shared container that neither of us has to maintain alone. The conversation itself becomes the infrastructure.

This explains why phone calls feel easier to me than texts, even though most people my age have decided phone calls are intrusive relics of a bygone era. For them, async is convenience—respond when you want, no pressure, no synchronization required.

For me, async is suspended animation.

That text thread sits there, frozen, requiring me to thaw and reanimate it every single time. My nervous system registers that dormant thread as an open loop—unresolved, cognitively expensive to close, mildly threatening.

Multiply that by 47 threads, and you’ve got a background hum of low-grade guilt that never quite goes away.

The Quality Problem

Looking back at that journal, there’s another pattern I didn’t recognize at the time.

August 4, 1997: “I really love it when it’s just me and her talking. I think she has finally realized that I’m understanding and will listen.”

I wrote that about my friend Kellie. But here’s the context: I’d been repeatedly leaving group hangouts because I couldn’t get real connection. When she was with her boyfriend, I’d bail. When parties got chaotic, I’d walk to my aunt’s house to fix her computer instead. When everyone was drunk and distracted, I’d page my buddy Beau with a series of yes-or-no questions until he figured out I needed extraction.

I wasn’t antisocial. I was connection-selective.

Group hangs with fragmented attention felt worse than being alone. But one-on-one, in real-time, with someone’s full presence? That’s where I came alive.

The same pattern shows up in how I processed those relationships. September 1997: “I always know what she’s thinking too. Probably just because I’ve done so much journal research on her and I’ve known her for so long.”

I called it “journal research.” I was sixteen. I didn’t have the language for what I was actually doing: building external models of the people I cared about because my internal working memory couldn’t hold them on its own.

The Attachment Layer

There’s another piece to this. I have an anxious attachment style and a core wound around feeling unseen or misunderstood.

Synchronous communication provides immediate relational feedback. I know in real-time that I’m being heard. I can course-correct if something lands wrong. The connection is live.

Asynchronous communication introduces uncertainty gaps that my nervous system interprets as ambiguous rejection:

Did they see it? Are they ignoring me? Was that last message weird? Should I double-text or would that be too much?

Each open thread becomes a tiny Schrödinger’s box of relational anxiety.

No wonder I made those “rounds” in 1997. My teenage brain had already figured out what my adult brain needed three decades to articulate: I require real-time co-regulation of context. It’s not a preference. It’s infrastructure.

I’m Not Broken. I’m Adapted.

For most of my life, I thought the problem was me. Not organized enough. Not disciplined enough. Not good enough at the basic social contract of modern communication.

But sixteen-year-old me already knew something was different. July 30, 1997: “That’s what you call a natural tweaker.” I was describing why I couldn’t sleep, why my brain wouldn’t stop processing. In the same entry: “No one will ever figure me out, even after reading this journal.”

And this one, from September: “Whenever she is fighting with Jeremy, I always get a sick feeling in my stomach and I call down to her house. I’m always correct.”

I called it ESP (the term for a sixth sense we used in the 90s). It wasn’t. It was pattern recognition running on overdrive—a brain that couldn’t stop processing relational data, even (especially) when I wasn’t consciously trying.

Here’s the reframe: I’m running specialized cognitive hardware in a world that’s shifted to async-first.

It’s not that I’m bad at relationships. It’s that I need synchronous connection to maintain them, and modern communication defaults have made that harder to access without feeling like you’re imposing on someone’s time.

The 47 unread messages aren’t evidence of my failure. They’re evidence that the dominant communication paradigm doesn’t match my cognitive architecture.

Building the Bridge

I’m not writing this just to explain a problem. I’m building a solution.

Remember that “journal research” I mentioned? At sixteen, I was already trying to build external models of the people I cared about—writing down patterns, tracking emotional states, creating infrastructure for relationships my working memory couldn’t maintain on its own.

Twenty-eight years later, I’m doing the same thing with better tools.

I’ve been developing a personal AI system called jonmick.ai that stores all of my contacts, text messages, and life context in one place. The idea is that my AI agent will eventually help me respond to messages quicker and more authentically—handling the reconstruction tax on my behalf so I can engage with the relationship instead of drowning in the cognitive overhead.

It’s not about outsourcing connection. It’s about removing the barriers that prevent me from showing up for the people I care about.

Because here’s what I know: I want to be a good friend. I want to stay in touch. I want to text you back.

I just need infrastructure that meets my brain where it actually is—the same infrastructure I was instinctively trying to build with a private phone line and a spiral-bound journal in 1997.

If this resonated, you might be someone who experiences working memory fragility too. I’m building AIs & Shine to create the cognitive scaffolding that minds like ours deserve.